Andrew Carnegie’s life is a remarkable testament to the power of ambition and resilience. Born into poverty in Scotland, he would go on to become the wealthiest man in the world. However, his story is not without its complexities and contradictions. In this article, we will explore the contrasting facets of Andrew Carnegie’s life, from his questionable treatment of workers to his extraordinary philanthropy efforts. Join us as we delve into the captivating tale of a man who shaped America’s industrial landscape and left an indelible mark on the world.

The Harsh Beginnings

Andrew Carnegie’s journey began in 1835, in the midst of abject poverty. Born in Scotland, his early years were marked by destitution and despair. The Carnegie family resided in a cramped cottage, sharing their meager dwelling with another family. Andrew’s father worked as a handloom weaver, but their lives took a dramatic turn when the advent of the industrial revolution rendered his skills obsolete.

With the family’s income stripped away, Andrew’s mother took on the burden of providing for her loved ones. She toiled tirelessly, repairing shoes for the local community, while Andrew witnessed his father desperately seeking employment. This haunting sight left an indelible mark on young Andrew’s impressionable mind.

The Journey to America

Recognizing that Scotland held no future prospects for their family, Andrew’s mother made a life-altering decision. Encouraged by stories of opportunity in America shared by her sisters, the family sold their belongings and embarked on a perilous journey to the United States in 1848. Their destination was Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a bustling center of manufacturing and industry.

Life in Pittsburgh proved to be a challenging endeavor for the Carnegie family. Andrew’s parents struggled to secure stable employment, compelling young Andrew to leave school after just five years of education. He shouldered the responsibility of finding work, knowing that his family’s survival depended on his efforts to generate additional income.

A Humble Beginning in the Cotton Mill

At the age of 12, Andrew Carnegie found himself working in a cotton mill, laboring 12 hours a day for a meager wage of $1.20 per week. Despite the harsh conditions, Andrew took pride in being able to contribute to his family’s well-being. He often reflected that his first paycheck brought him unparalleled happiness, as it signified his role in supporting his loved ones.

From Boiler Stoker to Engineer’s Assistant

Andrew’s dedication did not go unnoticed, and he quickly advanced to become an engineer’s assistant in a textile factory. While the pay was marginally better, the job took a toll on his well-being. Nightmares of accidents and being engulfed in flames haunted him. This challenging experience pushed him to seek new opportunities that would not only offer better compensation but also align with his aspirations.

A Messenger Boy and Networking Opportunity

At the age of 14, Andrew seized a chance to work as a messenger boy at a local telegraph office. In addition to a higher weekly pay of $2.50, this role allowed him to interact with influential individuals within Pittsburgh’s business community while delivering telegrams. Andrew’s shrewdness and determination led him to memorize the names and faces of the city’s most important figures, enabling him to make a lasting impression when encountering them on the streets.

Catching the Eye of a Railroad Manager

Andrew’s strategic approach paid off when Thomas Scott, a regional manager for the Pennsylvania railroad company, noticed his exceptional qualities. Tom became intrigued by Andrew’s potential and hired him as his personal telegrapher and private secretary. With this position, Andrew’s monthly wages increased significantly to $35. Furthermore, he gained a rare opportunity to observe the inner workings of a major corporation firsthand.

Tom Scott recognized Andrew’s ambition and work ethic, leading him to become a mentor figure in Andrew’s life. The mentorship between the two individuals flourished, with Tom seeing a reflection of his own humble beginnings in Andrew’s journey. As Tom ascended to the presidency of the Pennsylvania railroad company, Andrew’s career trajectory paralleled his mentor’s success. Andrew rapidly climbed the company’s ranks, assuming responsibilities in overseeing railroad expansion and gaining invaluable insights into running a profitable business.

Tom Scott and Andrew Carnegie shared a close bond, with Tom affectionately referring to Andrew as “my boy Andy.” This relationship went beyond professional guidance and showed a genuine camaraderie between the mentor and protégé. Their connection played a significant role in shaping Andrew’s future and instilling in him the knowledge and skills required for success.

While Andrew’s prospects were looking brighter, tragedy struck his family when his father, worn down by the industrial revolution, passed away at the age of 51. Witnessing his mother’s sorrow, Andrew made a solemn vow to become wealthy and ensure her well-being. Little did they know the extraordinary events that would soon unfold, taking Andrew’s journey to unimaginable heights.

The Bond Between Mentor and Protege

Working alongside Tom Scott, Andrew played an instrumental role in revolutionizing the railroad industry. Through their collaborative efforts, they developed larger cars and longer trains, which allowed for increased load capacity and reduced costs. Furthermore, their railroad became the first to operate trains continuously, 24 hours a day. Andrew’s involvement not only expanded his knowledge of business but also deepened his understanding of financial matters.

One day, Tom approached Andrew with a lucrative stock tip: Adam’s Express. Without hesitation, Andrew invested in this stock, which quickly skyrocketed, introducing him to the concept of making money effortlessly. Although this incident involved blatant insider trading, Tom’s influence planted the seed of the idea that money can work for you, rather than you working tirelessly for money, as Andrew had done in the past.

Assisted by his mentor, Andrew steadily climbed the ranks at the railroad company, experiencing a remarkable improvement in his financial standing. As he progressed, Andrew realized that his growing wealth presented an opportunity during the American Civil War in 1861. Instead of joining the battlefield himself, he paid a substitute to take his place. By the age of thirty, Andrew was earning an impressive annual income of over $50,000. However, he remained ever-vigilant for the next significant opportunity.

Transition to New York City and Pursuit of Luxury

With his newfound prosperity, Andrew decided to bid farewell to the Pennsylvania Railroad and embark on a new chapter in New York City, accompanied by his mother. They settled into a luxurious suite at one of the city’s most prestigious hotels, allowing Andrew to fulfill his desire to provide his mother with a taste of true luxury.

Upon arriving in New York, Andrew assumed the management of The Keystone Bridge Company. This venture stemmed from his previous experience at the railroad, where he recognized the need for iron bridges to replace wooden ones. However, The Keystone Bridge Company went beyond constructing bridges. Andrew applied the valuable lessons from his mentor and implemented vertical integration, establishing their iron mills for a self-sufficient supply of iron. This strategic move granted him greater control over production, cost reduction, and the ability to offer competitive prices, thereby solidifying his dominance in the market.

Leveraging Railroad Connections and Expanding Horizons

Andrew possessed a valuable advantage over his competitors: extensive connections within the railroad industry. Leveraging his previous associations, he successfully sold numerous bridges to rail companies seeking to expand their networks, enhancing his reputation and further establishing his company’s prominence.

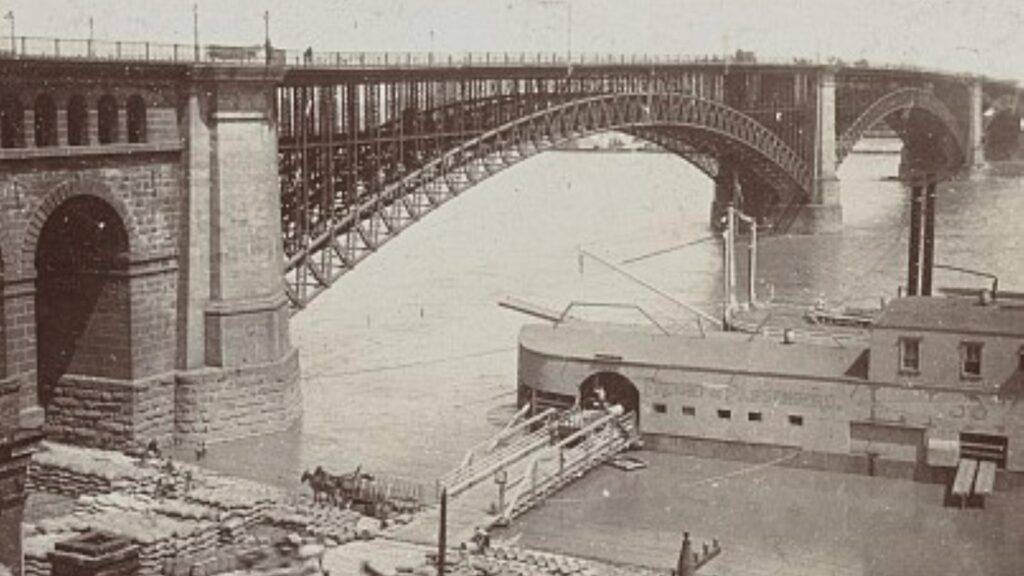

Andrew encountered a groundbreaking proposition—to construct the largest rail and road bridge in America at that time, spanning over a mile and connecting the East and West. However, the monumental challenge soon became apparent. Traditional bridge designs could not withstand the powerful currents of the Mississippi River. To overcome this obstacle, Andrew recognized the need for a stronger building material: steel. Despite its exorbitant cost and limited production capabilities, Andrew’s visionary approach drove him to consider steel as the solution for this ambitious project, transcending its conventional usage in cutlery and jewelery.

Discovering the Bessemer Process: A Turning Point

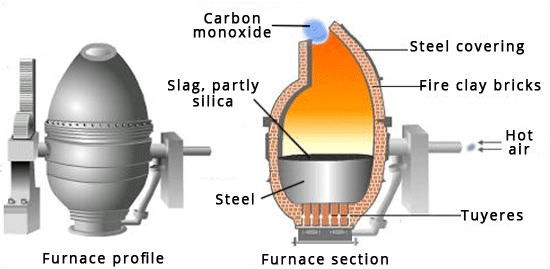

Andrew’s unwavering conviction in the power of steel led him on a nationwide exploration of steel mills and chemistry labs. Despite setbacks and disappointments, fate intervened when he was introduced to Henry Bessemer, a brilliant English inventor. Bessemer had devised a revolutionary method of refining steel from molten pig iron, surpassing existing techniques in efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

The Bessemer converter, a pear-shaped furnace, unlocked unprecedented possibilities for steel production. It slashed the manufacturing time of a single steel rail from two weeks to a mere 15 minutes, defying all prior beliefs. Andrew recognized that this breakthrough was the missing piece he needed to realize his vision. Driven by his unwavering determination, he invested nearly all his resources in adopting Bessemer’s innovative technology and adapted it to his own requirements.

From Vision to Reality: Establishing the Steel Mill

Andrew’s audacious commitment to his idea set him apart from other entrepreneurs. Undeterred by the risks, he embarked on the construction of a colossal steel production plant, a venture that only a few were willing to undertake. Fuelled by pure belief in the potential of steel, Andrew gathered additional investors to finance his ambitious project. Waste no time, he set up his first steel mill, equipped with Bessemer converters capable of producing vast quantities of steel.

Years of relentless work culminated in the successful completion of the bridge over the Mississippi River – an engineering marvel and the first-ever steel structure of such magnitude. However, one significant obstacle remained: public skepticism about the bridge’s safety. Collapsing bridges were not uncommon during that era, and the public was apprehensive about traversing such a colossal span. Andrew had to find a way to dispel their fears and establish the bridge’s credibility.

At the time, a popular superstition prevailed that elephants would refuse to walk across unstable foundations. Andrew seized upon this belief and devised a remarkable plan for the bridge’s grand opening. As the public gathered, eager to witness the bridge’s inaugural moments, Andrew orchestrated a parade led by a circus elephant. The majestic creature confidently strode across the bridge, proving its stability to the awestruck spectators. With their fears assuaged, people followed suit, and the Eads Bridge was officially open for business.

The completion of the Eads Bridge marked a significant milestone for Andrew and the steel industry. Carnegie steel, produced in Andrew’s mill, had showcased its immense potential. With the ability to manufacture steel on such a grand scale, Andrew set his sights on larger projects. Thanks to the Bessemer process, creating massive steel structures became a reality. The railroad industry became Andrew’s primary customer, eager to replace their outdated bridges and rail lines with affordable, robust, and reliable steel.

Andrew Carnegie’s Strategic Naming Decision

In a shrewd and unconventional move, Andrew, fully aware of the potential demand from railroads, made a strategic decision regarding the name of his inaugural steel mill. Instead of choosing a self-centered title, he opted for “The Edgar Thomson Steel Works,” paying homage to the influential president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. By associating his mill with one of the most prominent figures in the railway industry, Andrew sought to demonstrate his deep appreciation for the rail business, ultimately attracting more customers. His intuition proved correct.

Without delay, Edgar Thomson himself promptly placed an order for 2000 steel rails from Andrew’s steel company. However, the cost-effectiveness of Andrew’s steel production was partially rooted in the exceptional efficiency of his plant. Having grown up in poverty, he had learned to value each penny, and this frugality persisted as he managed his steel enterprise. His guiding principle was to “watch the costs, and the profits take care of themselves.”

The Price of Affordability: Labor and Its Consequences

A dark aspect of Andrew Carnegie’s pursuit of affordability was the stringent labor practices employed at the Edgar Thomson Steel Works. Workers endured grueling conditions, including long working hours and minimal holidays. With just a single annual holiday on the 4th of July, employees toiled relentlessly, both physically and mentally.

Andrew Carnegie’s quest for cutting costs extended to the neglect of worker safety. Protective equipment and safety measures were sorely lacking, resulting in numerous injuries and even fatalities. Unfortunately, the priority placed on reducing expenses overshadowed the well-being of the workers.

Competitiveness and the Strain on Employees

Andrew Carnegie attempted to stimulate competition among workers by pitting them against each other. While this initially led to record-breaking steel production, it created a new standard quota for workers to meet consistently. Failure to meet these targets resulted in termination, leading to a high turnover rate and strained workforce.

Carnegie intentionally employed unskilled laborers for repetitive tasks to ensure easy replacementability. Consequently, workers felt deprived of any pride or craftsmanship in their work, leading to a sense of dehumanization. This approach, although successful in boosting efficiency, came at the cost of the workers’ well-being.

Despite the controversial labor practices and cost-cutting measures implemented at the Edgar Thomson Steel Works, Andrew Carnegie’s unwavering commitment to efficiency undeniably propelled his mill to unprecedented productivity. While it is crucial to understand the historical context and acknowledge the harsh realities of the era, Carnegie’s relentless drive for success ultimately led to the mill’s capacity to produce an astounding 225 tonnes of steel per day. The legacy of the Edgar Thomson Steel Works serves as a testament to the intricate relationship between efficiency, labor practices, and industrial progress in the 19th century.

The Pursuit of Efficiency: Embracing Technological Advancements

Andrew Carnegie’s success can be attributed, in large part, to his unyielding focus on maximizing efficiency. Recognizing the potential of technological advancements, he embraced machinery as a means to streamline production processes and minimize costs. Carnegie firmly believed that machines, devoid of human limitations, were the key to unlocking unparalleled productivity.

To achieve this goal, Carnegie eagerly sought out new technologies that could replace labor-intensive tasks. He willingly discarded outdated processes, plants, or departments if superior alternatives were available. Renowned for his decisive and swift decision-making, Carnegie became synonymous with efficiency in the industry.

One notable innovation was the implementation of advanced material handling systems. Carnegie introduced overhead cranes and hoists, revolutionizing the steelmaking process. These new systems expedited production, significantly increasing the mills’ capacity to meet the nation’s growing demand for steel.

Vertical Integration: Controlling the Supply Chain

Central to Carnegie’s business philosophy was the concept of vertical integration. He aimed to exert control over every aspect of the steel production process, from acquiring raw materials to transporting finished goods. By vertically integrating his operations, Carnegie could eliminate intermediaries, reduce costs, and solidify his dominance in the industry.

Carnegie’s pursuit of vertical integration extended beyond the steel mills. He recognized the importance of securing a reliable supply of raw materials, such as iron ore and coal. To accomplish this, he acquired mines, ensuring a constant flow of essential resources. Additionally, Carnegie ventured into the transportation sector, seeking ownership of railroads to facilitate the efficient distribution of his steel products to customers across the nation.

By effectively managing all stages of production and distribution, Carnegie achieved unparalleled cost savings and gained a competitive edge over his rivals. His relentless drive for control and efficiency solidified his position as a titan of the steel industry.

A Change of Heart: The Promise of Benevolence

Interestingly, at the age of 33, Andrew Carnegie wrote a letter to himself, pledging to devote his life to “benevolent purposes” after just two more years of work. In this introspective moment, he acknowledged that the relentless pursuit of wealth could have a detrimental effect on his character.

Despite his intentions, Carnegie found himself entangled in controversies and faced with new challenges as the years went by. The two-year deadline came and went, and his dedication to the steel industry persisted, overshadowing his initial aspirations.

The Railroad Dilemma: A Test of Resilience

Following a period of remarkable success in the steel business, Andrew Carnegie encountered a sudden setback—the railroad industry, his biggest customer, faced a series of daunting obstacles. The rapid expansion of railroads resulted in an oversaturated market, with numerous competing lines vying for business. As economic activity slowed and the stock market crashed, the railroads found themselves grappling with financial instability.

The ensuing economic depression presented a daunting challenge for Andrew Carnegie. The railroads, crippled by financial woes, could no longer afford to purchase substantial quantities of steel, jeopardizing Carnegie’s business model, which relied on high-volume sales.

Amidst this turmoil, oil magnate John D. Rockefeller recognized an opportunity to exploit the railroads’ desperation for cargo transportation. Rockefeller negotiated a significant discount, allowing him to ship vast quantities of oil at substantially lower prices. The railroads, desperate for revenue, initially accepted the offer, albeit at a heavy cost to their sustainability.

However, the unsustainable nature of the discount soon became evident, prompting the railroads to seek renegotiation. Unfortunately, Rockefeller refused to compromise, choosing instead to withdraw his oil shipments entirely. This decision had disastrous consequences, causing numerous rail companies to go bankrupt and intensifying the industry’s crisis.

A Desperate Plea: Tom Scott and Andrew Carnegie

One individual severely affected by the railroads’ struggles was Tom Scott, Andrew Carnegie’s former mentor. Scott, who had invested in multiple railroads, found himself in dire straits. Realizing Carnegie’s prosperous venture into the steel business, he turned to his protégé, seeking financial assistance to prevent his rail company from going under.

This time, the tables had turned, and it was Carnegie who was being asked for help. The request posed a significant dilemma for Carnegie, as investing in the struggling rail company could potentially jeopardize his own steel empire. The decision he faced would shape the course of his legacy and cement his position as one of history’s most influential industrialists.

Andrew’s reluctance to assist his former mentor, who had played a significant role in his life, was unexpected. He cited his financial entanglement in the manufacturing sector as the reason for his inability to help.

This rejection left Tom devastated, and tragically, his business never managed to recover. Shortly after, Tom passed away, leaving a void in Andrew Carnegie’s life. The individual who once held immeasurable importance to him was now gone forever.

The Rise of a Bitter Rivalry

Standing in the pouring rain at Tom Scott’s grave in 1881, Andrew firmly believed that Rockefeller bore the responsibility for his mentor’s untimely demise. Perhaps it was Andrew’s way of deflecting any accountability from himself, but he became convinced that Rockefeller had driven Tom Scott to his grave, fueling a desire for vengeance within him.

And thus, a rivalry was born: the clash between the oil magnate and the steel tycoon.

The bitter rivalry between two industrial titans, Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, defined an era of American history. From their humble beginnings to their immense wealth, their paths intertwined, fueled by ambition, revenge, and a desire for dominance. This belief ignited a burning desire for revenge, setting the stage for a rivalry that would shape the landscape of American business. While their feud was marked by tension and animosity, it also had its lighter moments, with passive-aggressive Christmas gifts exchanged between the two. Yet, it was the competition between these two titans that propelled them to greater heights, forever changing industries and leaving a lasting legacy.

The Emergence of a Steel Empire

As the railroad industry faced challenging times, Andrew Carnegie recognized a new market opportunity. The influx of unemployed Americans into major cities like Chicago and New York presented a chance to revolutionize urban architecture. Carnegie foresaw the need for skyscrapers and realized that steel could be the key to constructing taller, more secure structures. Capitalizing on this insight, his steel company embarked on a monumental endeavor, erecting tens of thousands of skyscrapers across the nation. The landscape of America was transformed, and Carnegie’s profits soared. However, despite his financial success, he still trailed behind Rockefeller’s immense wealth, spurring Carnegie’s determination to surpass his rival and avenge his mentor.

The Arrival of a Ruthless Partner: Frick and Devastating Consequences

In his pursuit of greater profitability, Andrew Carnegie sought the assistance of Henry Clay Frick, an industrialist notorious for his cutthroat business tactics. Frick, driven by his ambition to become a millionaire before the age of 30, was known for his ruthless nature and relentless pursuit of success. While Carnegie was sensitive to public opinion, Frick operated without regard for public sentiment. Believing that a partnership with Frick would provide his company with a decisive edge, Carnegie invited him to oversee his steel mills.

Frick wasted no time in proving his worth. Through intimidation, he renegotiated improved contracts with suppliers, reducing costs and eliminating waste. Furthermore, by positioning Frick as the public face of the company, Carnegie skillfully shifted blame and criticism away from himself. For instance, despite record-breaking profits, worker wages were further reduced. Carnegie managed to distance himself from this decision, attributing it to Frick. This arrangement allowed him to protect his public image while maximizing his company’s profitability.

For instance, despite achieving record-breaking profits, they decided to further reduce worker wages. Andrew successfully portrayed this decision as Frick’s doing, with Frick assuming the responsibility of delivering the distressing news.

Similarly, Frick had gained notoriety for dismantling unions and squashing any attempts by workers to unite. As a result, most of Carnegie’s steel mills operated without any labor unions.

Ruthlessness Unleashed: Duquesne Steelworks

One notorious example of Carnegie and Frick’s ruthless tactics occurred when Duquesne steelworks emerged as a formidable competitor. Duquesne employed innovative technology and cost-cutting systems that threatened Carnegie’s dominance. Fearing a fair fight, Carnegie and Frick conspired to undermine Duquesne’s reputation.

With Frick’s assistance and their extensive network of contacts, Carnegie initiated a campaign to spread baseless rumors about Duquesne’s steel quality. By circulating a note among various railroads warning them about the supposed lack of “homogeneity” in Duquesne’s steel, Carnegie created an atmosphere of doubt and fear. This cunning strategy deterred potential customers from purchasing Duquesne’s steel, severely impacting their sales and profitability.

Undercutting Prices to Accelerate Demise

Understanding that a decline in sales would ultimately render Duquesne unprofitable, Carnegie temporarily undercut their prices to attract customers. Despite incurring losses, Carnegie aimed to snatch Duquesne’s customers and drive them out of business. In less than a year, these calculated moves led to the financial ruin of Duquesne steelworks, presenting an opportunity for Carnegie and Frick to capitalize on the situation.

Duquesne’s Steelworks Acquisition

With Duquesne on the brink of collapse, Frick skillfully negotiated a deal for Carnegie and himself to purchase the steelworks at a significantly reduced price. This acquisition not only eliminated a fierce competitor but also granted Carnegie and Frick access to the cost-cutting techniques previously employed by Duquesne. Paradoxically, the very methods they had discredited earlier became the foundation for enhancing efficiency and profitability in their other steel mills.

The Duquesne ordeal was just one example of Carnegie and Frick’s relentless pursuit of success. Their unscrupulous actions extended beyond spreading rumors, and their dubious practices would continue to tarnish their legacies.

Despite the controversies surrounding their methods, the partnership between Carnegie and Frick yielded substantial financial gains. By increasing production and slashing costs, they nearly doubled profits within the first year of working together. The increased capital allowed them to acquire additional competitors’ businesses, expand their steel mill operations, and contribute to Carnegie’s ever-growing personal fortune, potentially making him a billionaire by today’s standards.

However, the calamitous events surrounding the South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club would unravel their fortunes, leading to tragedy and public outrage.

The Birth of a Catastrophe: The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club

The South Fork Fishing and Hunting Club emerged as a luxurious retreat nestled in Pittsburgh’s hills, catering exclusively to the nation’s wealthiest industrialists, bankers, and influential figures. At the helm of this exclusive haven was Henry Frick, accompanied by his esteemed partner, Andrew Carnegie. Taking control of the South Fork dam, a colossal structure holding 20 million tonnes of water, the club aimed to create a private fishing paradise.

In their pursuit of perfection, the club prioritized their own desires over the safety of the dam. Disregarding expert advice, they made ill-advised alterations, such as flattening the dam’s top to accommodate a road and lowering its height by several feet. Despite local officials’ pleas for reinforcement, the club remained indifferent to the potential consequences. The dam’s stability was compromised, unbeknownst to the unsuspecting residents downstream.

The Tragedy Unfolds – The Johnstown Flood

In 1889, a fateful rainstorm battered the region, triggering a catastrophic breach in the weakened dam. Millions of gallons of water surged toward Johnstown, a town primarily inhabited by hardworking steelworkers and their families, located just 14 miles downstream. The torrent unleashed devastation, claiming the lives of 2,209 people, including 400 innocent children. The aftermath was harrowing, as bodies scattered across vast distances, washing up even hundreds of miles away.

While Andrew Carnegie himself did not have direct involvement in the dam’s ill-fated alterations, his close association with Frick and membership in the club proved detrimental to his reputation. Faced with the daunting task of safeguarding Frick’s interests, Carnegie participated in concealing the club’s negligence. This unfortunate association tarnished Carnegie’s image in the eyes of the media and the public, igniting a storm of criticism.

The Johnstown flood served as a stark reminder of the perils of unchecked privilege and negligence. The club’s affluent members, wielding their considerable wealth, skillfully avoided accountability for their actions, further fueling public outrage. While Carnegie himself did not bear direct responsibility for the tragedy, his affiliation with the club left an indelible mark on his reputation. The media and society at large condemned his association, casting a shadow over his achievements and philanthropic endeavors.

Andrew’s Growing Fortune, Workers’ Struggle

Andrew’s workers found themselves trapped in a disheartening cycle of limited prospects and stagnant wages. Their sense of frustration and helplessness stemmed from witnessing Carnegie’s wealth soar while they struggled to make ends meet. Paradoxically, despite publicly advocating for workers’ right to organize, Andrew’s company relentlessly sought to suppress unionization efforts, fueling the simmering discontent among his employees.

Andrew’s construction of a library near his first steel mill, the Edgar Thomson steelworks, presented an illusion of benevolence towards his workers. However, the reality was far from the facade he portrayed. The grueling working hours imposed on employees rendered the library practically inaccessible, and the majority of his workforce consisted of illiterate laborers. The library, rather than addressing workers’ needs, seemed more like a calculated move to safeguard his reputation, diverting attention from the genuine concerns and demands of his employees.

Andrew Carnegie relished being perceived as a magnanimous figure, inaugurating libraries with grand ceremonies and publicly advocating for workers’ rights. Yet, behind closed doors, he conveniently assigned Henry Frick the role of implementing unpopular decisions and bearing the blame for the harsh treatment of workers. Frick’s reputation as a ruthless enforcer seemed to suit Carnegie’s ulterior motives, allowing him to maintain a carefully crafted image while distancing himself from the unpopular actions taken against the workers.

The Homestead Steel Plant Dispute

The Homestead steel plant acquisition marked another milestone in Carnegie’s growing steel empire. As the plant flourished, labor costs became a focal point for optimization, leaving the workers’ union, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers, eager to negotiate a wage increase. However, Andrew, keen on reshaping his public image, had no intention of acceding to their demands.

In an attempt to reconcile his image as a benevolent champion of workers’ rights with his true intentions, Andrew suggested building a library near the Homestead steel plant but made it contingent upon the workers severing their ties with trade unions. Recognizing the potential hostility of the negotiations, Andrew distanced himself from the dispute, conveniently leaving Henry Frick in charge. With Andrew’s unequivocal support, Frick would do what was necessary to maintain Carnegie’s desired outcome.

Andrew Carnegie’s Role in the Homestead Strike

Despite outwardly distancing himself from the situation, Andrew Carnegie secretly ordered Henry Frick to dismantle the union at the Homestead steel plant. This stark contrast between Carnegie’s public support for workers’ rights and his private directive to crush the union exposes his true intentions.

Prior to leaving for his vacation in Scotland, Carnegie issued another instruction to Frick: intensify production levels at the plant, ensuring a surplus of materials in case negotiations failed and a strike ensued. Consequently, the workers were subjected to grueling conditions, with longer workdays leading to heightened exhaustion and an increased risk of accidents and fatalities.

The Homestead workers endured dismal conditions for meager wages, witnessing their colleagues suffer accidents or even lose their lives. Their workdays extended without any corresponding pay increase, resulting in extreme physical and mental strain.

As their contract neared expiration, the union demanded improved safety conditions and a raise in wages. However, their hopes were dashed when Henry Frick responded by proposing a 22% wage decrease and asserting that the union had to be dissolved for the workers to continue employment at the plant. This unfair proposition further exacerbated the workers’ already dire circumstances.

Carnegie’s Betrayal and the Workers’ Resolve

In a desperate attempt to seek support, the workers turned to Andrew Carnegie, the primary owner of the mill, who had previously shown sympathy towards unions and laborers. However, to their dismay, Carnegie proved unresponsive, conveniently inaccessible during his Scottish vacation. This apparent betrayal left the workers feeling abandoned and disillusioned.

While publicly silent, Andrew Carnegie maintained communication with Henry Frick from his Scottish castle. In a series of letters, he unabashedly expressed his unwavering support for Frick’s actions, stating, “Mr. Frick, no doubt you will get Homestead right. You can get anything right with your mild persistence. We all approve of anything you do. We are with you to the end.” These private correspondences shed light on Carnegie’s true allegiance, leaving no doubt about his siding with Frick.

The Homestead Steel Mill Strike: A Battle for Workers’ Rights

While negotiations between the steelworkers’ union and the mill’s management, led by Henry Frick, seemed at an impasse, the union expressed its willingness to compromise on most of Frick’s demands. They recognized the importance of finding common ground but remained steadfast in their resolve to maintain their union rights.

In stark contrast to the union’s willingness to reach a compromise, Frick displayed an unwavering determination to secure a victory. He rejected any notion of compromise, driven by his desire to come out on top. The path he chose was one of confrontation and domination.

On June 29th, Frick, under the directive of Andrew Carnegie, made the bold move of closing down the Homestead steel mill. With this action, he aimed to force the workers into submission, hoping they would abandon their union and return to work without an increase in pay. Frick even threatened to replace the striking workers with non-union immigrant laborers, prioritizing the mill’s operations over the workers’ rights.

The Workers’ Resilience

Contrary to Frick and Carnegie’s expectations, the workers were united in their conviction. Having dedicated themselves to the mill and contributed significantly to its success, they believed they deserved a fair share of the benefits. Thus, they chose to go on strike, seizing control of the mill and obstructing any attempts to replace them.

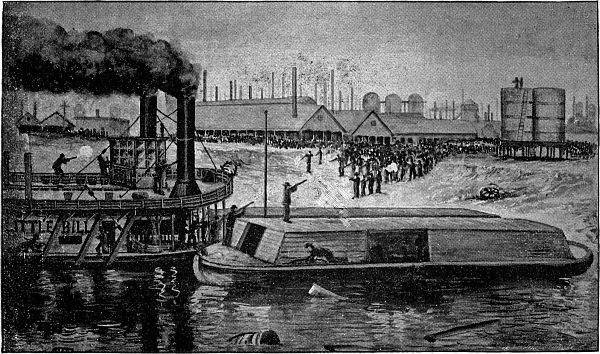

Unyielding in his pursuit of victory, Frick enlisted the services of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, effectively assembling a private mercenary force. The Pinkertons were tasked with escorting the immigrant workers hired to replace the striking employees. Frick hoped that the sight of armed Pinkertons would intimidate the workers into surrendering.

On July 6th, 1892, the Pinkertons arrived by boat, numbering around 300 strong. Unbeknownst to them, the striking workers stationed along the river had caught sight of their arrival. Word spread among the thousands of strikers, urging them to arm themselves and prepare for a confrontation.

As the Pinkertons disembarked from their barges, one of the striking workers pleaded with them not to proceed. He warned of the weapons possessed by the strikers and implored them to avoid escalating the situation. Regrettably, the Pinkertons remained steadfast in their mission, adhering to Frick’s orders to reclaim control of Homestead.

The precise trigger for the start of the conflict remains a matter of historical debate. Nevertheless, it is evident that chaos swiftly consumed the area surrounding the Homestead steel mill. The cacophony of stones, bullets, and anguished cries filled the air, marking the commencement of a fierce battle.

In an act of defiance, the striking workers launched a flaming freight train car towards the Pinkerton barges, showcasing their unwavering determination. To further disrupt the Pinkertons’ operations, they resorted to tossing dynamite into the river, aiming to sink their boats. In an audacious move, they even pumped oil into the river, attempting to set it ablaze.

The Pinkertons responded to the workers’ assault by firing their guns, instigating a chaotic and violent confrontation. The scene was fraught with tension and danger as both sides engaged in a fierce battle that would endure for a grueling 12 hours.

The Toll of Battle – Lives Lost and Communities Shattered

Amidst the relentless fighting, tragedy befell both sides. Tragically, it is estimated that nine Homestead workers lost their lives during the brutal conflict, while seven Pinkerton army men also met their demise. The toll of the battle extended beyond the loss of life, leaving countless individuals on both sides severely injured and scarred.

The aftermath of the battle was haunting, with the lifeless bodies of fallen fighters scattered across the battlefield. The once-vibrant landscape now stood as a grim reminder of the violence that had transpired, as the fallen lay motionless and brutally beaten.

The Unforeseen Outcome

Contrary to their expectations, the Pinkertons found themselves forced to surrender after enduring the striking workers’ fierce resistance. Initially hired by Frick with the assumption that the workers would not put up such a formidable fight, the Pinkertons were taken aback by the unwavering determination of the Homestead workers.

In the wake of their apparent victory, the workers held onto the belief that Frick would be compelled to negotiate with them. However, their hopes were dashed as they soon realized they had miscalculated. Frick remained steadfast and refused to engage in negotiations, leaving the striking workers disheartened and grappling with an uncertain future.

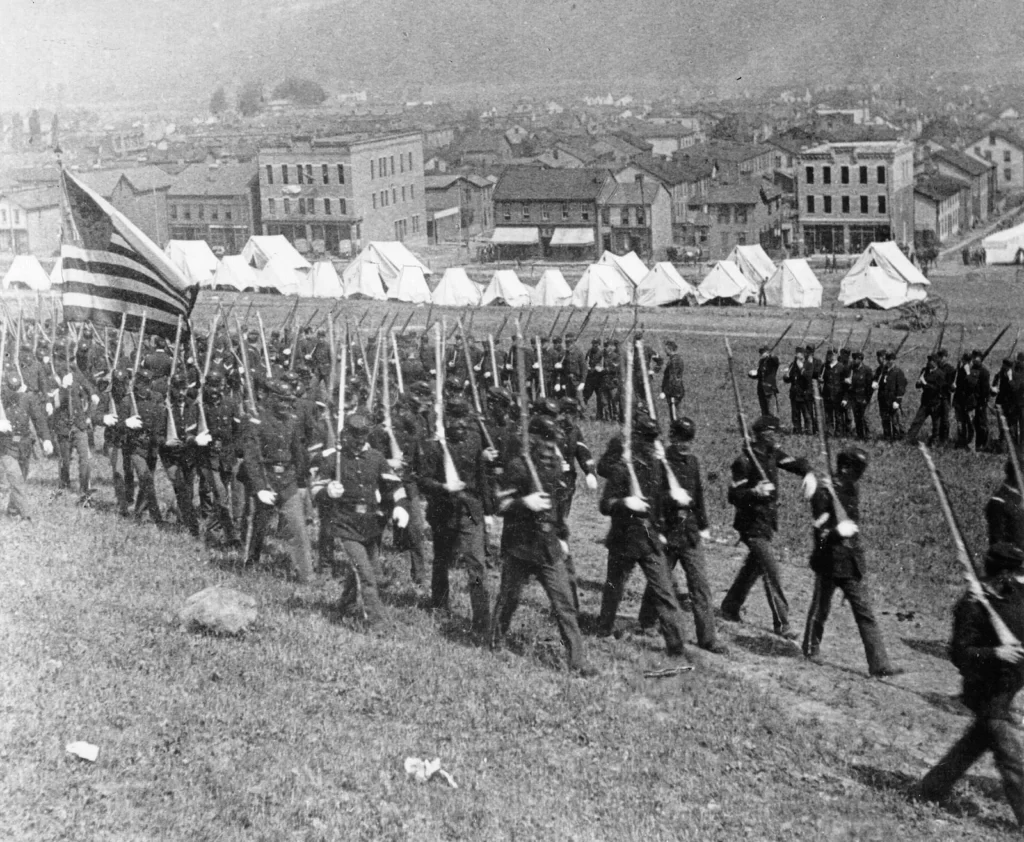

The Consequences of Andrew Carnegie’s Ambitions

The Pennsylvania governor, upon hearing of the escalating violence at Homestead, deployed the state militia consisting of eight thousand troops. However, instead of restoring order impartially, their primary objective was to reclaim the mill for Carnegie Steel. The outnumbered workers were eventually forced to leave, enabling Frick to reopen the steelworks with replacement laborers, leaving many Homestead workers unemployed and even homeless. Tragically, lives were lost during this tumultuous period.

While some original Homestead workers managed to retain their positions, they faced diminished wages, longer hours, and continued safety hazards. Moreover, they were coerced into signing ironclad contracts that effectively stripped away their rights to unionize. This pivotal strike left the steelworkers without a union for another 45 years, solidifying it as a turning point in American labor history and a resounding victory for Carnegie and Frick.

The Fallout – Carnegie’s Tarnished Image

Although Andrew Carnegie achieved his economic objectives, his carefully cultivated public image suffered a significant blow. The violence that transpired at Homestead sparked public outrage, causing Carnegie to prolong his stay in Scotland, hoping the controversy would eventually dissipate. However, the stain on his reputation endured. Labeled as the “arch sneak of this age” and accused of cowardice, Carnegie’s distancing from the events and his reliance on others to handle his affairs damaged his public perception.

To what extent can Andrew Carnegie be held accountable for the Homestead tragedy? In his autobiography, Carnegie vehemently denied any responsibility, portraying himself as a victim alongside the workers. He claimed ignorance and expressed deep wounds over the events. Nevertheless, evidence indicates that Carnegie had knowledge of Frick’s plan to suppress the union and consistently granted approval and assurance for whatever actions were deemed necessary.

Defending Carnegie, it is crucial to acknowledge his absence from Homestead during the strike. Had he been present, the outcome might have been different. Ultimately, it was Frick who engaged the Pinkerton detectives, with both Frick and Carnegie underestimating the potential for violence. Carnegie never intended nor anticipated bloodshed. Nevertheless, as the principal owner of the plant, he bears some responsibility due to documented correspondence that revealed his awareness of Frick’s plan.

Andrew Carnegie’s connection to the Homestead Strike cannot be overlooked. Despite his claims of being a bystander, his letters revealed a more active role. In one correspondence, he warned against employing the rioters and stressed the importance of not failing. This explicit statement raises questions about Carnegie’s true intentions and knowledge of the situation.

Andrew Carnegie’s decision to appoint Henry Frick, who had previously utilized Pinkertons for labor disputes, as the overseer of the Homestead situation was telling. Carnegie was well aware of Frick’s brutal methods and the potential consequences. He understood the tense atmosphere and the risk of escalation, yet he continued to encourage Frick through his letters. Carnegie’s actions demonstrate a degree of complicity and suggest he could have intervened to prevent the tragic outcome.

Carnegie’s Benefit from the Homestead Incident

While holding Andrew Carnegie solely responsible for the events at Homestead would be unfair, his claim of complete helplessness is dubious. Furthermore, it is undeniable that Carnegie reaped benefits from the incident. The strike dealt a significant blow to the unions, enabling Carnegie to further reduce costs. This newfound advantage allowed him to reinvest in expanding his empire and develop railroads for efficient transportation of goods from the plants.

Public sentiment towards the Homestead workers shifted as reports of violence and their assault on Pinkerton agents spread. However, support plummeted further when an unrelated anarchist attempted to assassinate Henry Frick as retaliation for his harsh treatment of workers during the strike. Despite failing to kill Frick, the incident influenced public opinion. Many recognized the economic advantages brought about by Carnegie’s low-cost steel, which weakened support for the unionized workers.

The Suppression of Workers’ Rights

In their efforts to maintain control, both Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick established an elaborate system of corporate spies within their steel mills. These spies provided continuous updates to management regarding any potential employee organization or attempts to unite. This system effectively crushed unionization efforts before they could gain momentum, leaving the workers powerless and their wages suppressed.

The presence of corporate spies bred fear among the workers, inhibiting communication and destroying any sense of community. The atmosphere was so tense that individuals were afraid to speak freely, leading to a prevalent saying at the time: “If you want to talk at Homestead, you must talk to yourself.” The divisive environment created by Carnegie and Frick shattered any hopes of solidarity among the workers.

Andrew Carnegie’s contradictory approach to the labor movement raises intriguing questions. His father, an advocate for improved working conditions, instilled in him the belief that workers deserved better. Yet, as a businessman, Carnegie recognized the necessity of driving down costs and maintaining a competitive edge. Throughout his life, he grappled with this internal conflict, torn between his genuine sympathy for workers and his drive for business success.

Andrew Carnegie’s Ambitious Return

After a few years, Andrew Carnegie returned to the homestead, embarking on an ambitious project. He opened an impressive edifice comprising a library, concert hall, swimming pool, and gymnasium. The grandeur of the building, however, failed to overshadow the damage caused by his actions during the strike.

During the building’s inauguration, Carnegie made a peculiar statement. He proclaimed, “By this meeting, all the regretful thoughts, all the unpleasant memories are forever in the deep bosom of the ocean, buried. Henceforth, we are to think of Homestead as we see it today.” Although his words sought reconciliation, they appeared more self-assuring than genuine, as if he was attempting to convince himself rather than others.

The Blame Game Begins

In an effort to rewrite history, Carnegie began speaking to the press, absolving himself of responsibility for the Homestead strike. He boldly asserted that, had he been present during the events, there would have been no bloodshed. He claimed respect for his workers, subtly implicating Henry Frick as the sole culprit.

Understandably, Henry Frick was outraged when he discovered Carnegie’s attempt to shift blame. He confronted Andrew, expressing his frustration with the hypocritical articles and absurd interviews. Frick demanded to know why Carnegie had not been forthright to his face. He declared, “I have stood a great many insults from Mr. Carnegie in the past, but I will submit to no further insults in the future.”

The clash over blame marked a turning point in the relationship between Carnegie and Frick. Subsequent incidents intensified their disagreements, and Frick ultimately resigned as chief executive. However, this resignation only triggered further turmoil, as a dispute emerged regarding the fair valuation of Frick’s shares.

Believing Carnegie aimed to swindle him, Frick accused his former partner of attempting to undervalue his shares. In their final meeting, Frick unleashed his anger, accusing Carnegie of lacking honesty and referring to him as a “god-damned thief.” As a result, Frick initiated a high-profile lawsuit, seeking compensation for the true market value of his shares.

A Legal Battle Unveils Secrets

The ensuing court battle gained widespread attention in national newspapers. The narrative of two industrial titans turned adversaries captured the public’s imagination, a tale of revenge, betrayal, and deceit. Furthermore, the lawsuit brought to light the financial details of Carnegie Steel, which had been shrouded in secrecy. It was revealed that the company was poised to make approximately $40 million in 1900, equivalent to a staggering 1.4 billion in today’s currency.

In an attempt to prevent further disclosure of private matters, a settlement was eventually reached. Frick agreed to be bought out for $31.6 million, relinquishing any management role and dropping his lawsuit against Carnegie. This agreement effectively silenced the contentious legal battle, but it forever severed ties between the two men.

Following their separation, Andrew Carnegie and Henry Frick never reconciled or met again. However, Frick took pleasure in taunting Carnegie from a distance. He would send mocking messages to Andrew, deriding his business decisions and stating, “Your management of the company has already become the subject of jest.”

In a final act of provocation, Frick commissioned a building next to one of Carnegie’s structures. To assert dominance, Frick insisted that his building be taller, casting Andrew’s edifice into its shadow, both literally and symbolically.

Andrew Carnegie Sells His Empire to J.P. Morgan

Amidst the turmoil of their severed partnership, Andrew Carnegie’s steel mills continued to flourish. By the turn of the 20th century, his company had surpassed even the production levels of the entire nation of Great Britain. Carnegie’s unwavering commitment to innovation and efficiency had cemented his status as an industry giant.

Approaching his 70s, Andrew felt the pressing need to spend more quality time with his family. His wife yearned for a life free from the shackles of constant work, urging him to sell his business. Although hesitant at first, Andrew gradually warmed up to the idea of parting with his beloved steel empire, envisioning a peaceful existence with his loved ones.

The Challenge of Finding a Buyer

Yet, selling such a colossal enterprise was no easy task. Andrew’s company held immense value, making it difficult to find a buyer with the means to acquire it. As the search for potential suitors commenced, it became evident that only a select few possessed the financial capacity to even consider such a venture.

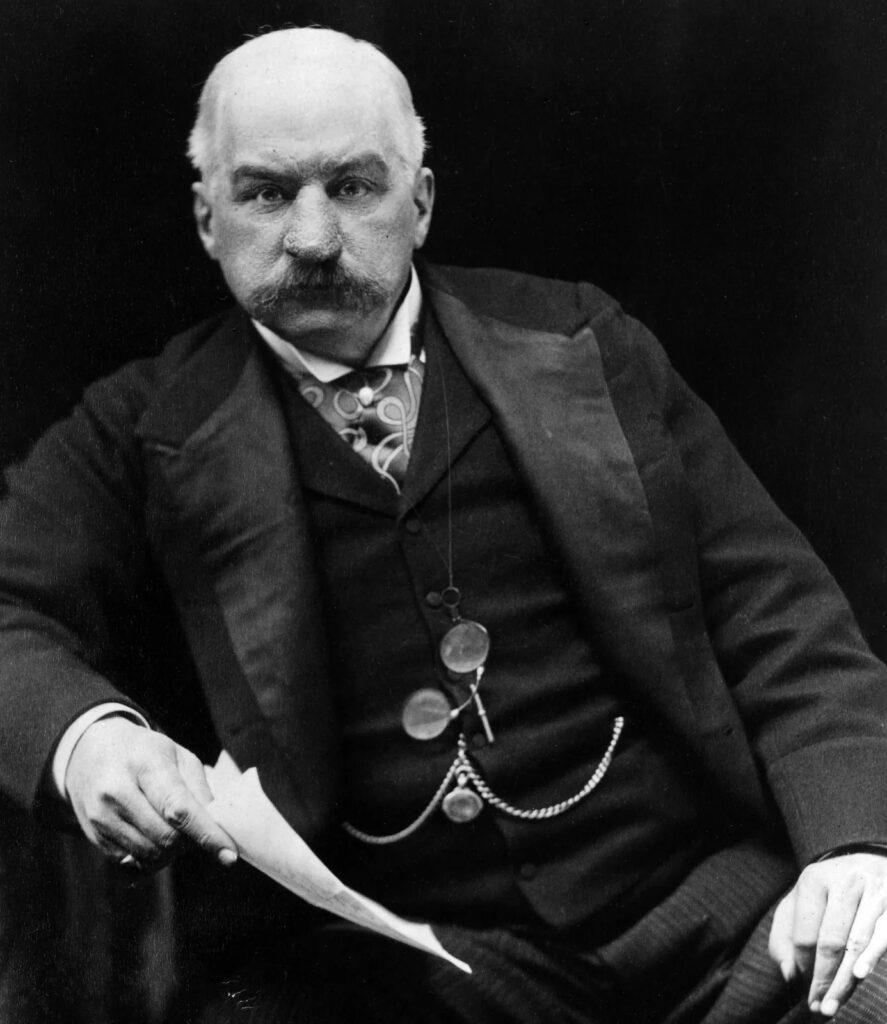

Among the limited pool of prospective buyers, one name stood out: John Pierpont Morgan, a renowned financier of extraordinary wealth. Morgan had already made a name for himself in the railroad industry, capitalizing on its downturn by acquiring undervalued railroads and merging them to create dominant conglomerates. With his sights now set on the steel industry, Morgan understood that acquiring Carnegie’s company would be more advantageous than attempting to compete directly with him.

It was through the mediation of Charles Schwab, then president of Carnegie Steel, that the deal between Carnegie and Morgan began to take shape. Schwab, who had succeeded Henry Frick, acted as the crucial intermediary connecting these two formidable magnates. First, he approached Morgan to gauge his interest, finding an eager potential buyer. Subsequently, Schwab presented the idea to Andrew Carnegie, setting the stage for a monumental transaction.

Legend has it that during a game of golf, Andrew Carnegie’s wife astutely advised Charles Schwab to broach the topic of selling Carnegie’s company when he was relaxed and in a good mood. This astute suggestion led to a pivotal moment that would change the course of history. In 1901, Charles Schwab, acting on behalf of JP Morgan, engaged Carnegie in a discussion about selling his steel empire. Andrew, known for his shrewdness, agreed to the idea under one condition – they had to agree on a suitable price.

The Historic Price Tag

JP Morgan, recognizing the opportunity, requested Andrew Carnegie to jot down the figure he desired for his business. With a stroke of a pen, Andrew inscribed the staggering amount of $480 million. In today’s terms, this astronomical sum would equate to approximately $17 billion, accounting for inflation. With an air of confidence, JP Morgan merely glanced at the paper and swiftly accepted the deal without hesitation. In a historic moment, the two magnates shook hands, sealing the agreement that would forever reshape American industry.

US Steel: The Birth of a Billion-Dollar Corporation

Following the completion of the deal, JP Morgan orchestrated the amalgamation of Carnegie’s steel company with various other steel enterprises, birthing the colossal US Steel. This groundbreaking merger solidified US Steel’s position as the world’s first-ever billion-dollar corporation. Meanwhile, Andrew Carnegie, having divested his steel business, ascended to the pinnacle of wealth and became the wealthiest individual in the world.

A Philanthropic Calling: Andrew Carnegie’s Benevolent Journey

While Andrew Carnegie had amassed unimaginable wealth, he harbored a desire to be remembered for the good he had done. Devoting himself to philanthropy, he embarked on a mission to distribute his vast fortune and effect positive change in the world. Recognizing that simple charity would not elevate individuals from their circumstances, Carnegie chose education as his primary focus. Despite receiving only five years of schooling himself, he attributed his financial success to the power of education.

Andrew Carnegie’s profound belief in education led him to establish over 2,500 libraries across various regions worldwide. These libraries served as gateways to knowledge and opportunity for countless individuals. Moreover, Carnegie’s philanthropic endeavors extended beyond libraries; he generously funded the establishment of museums, schools, and universities. One remarkable testament to his enduring impact is Carnegie Mellon University, a prestigious institution bearing his name. Remarkably, not all the libraries he founded carried his name; instead, he provided grants and funding to numerous institutions without seeking personal recognition.

The Philanthropic Legacy and Impact on Society

Carnegie Hall, one of New York’s most iconic landmarks, held a different title in 1891 when Andrew Carnegie donated the building. Initially known as “the music hall,” it was later named after Carnegie following his demise. Contrary to popular belief, Carnegie did not request the building to bear his name. Dismissing his generosity as mere self-preservation or ego would be unfair. Andrew Carnegie genuinely aimed to make a lasting impact and assist people in need. He held strong beliefs against passing on wealth to future generations, as he viewed inherited fortunes as a waste and saw heirs squander money self-indulgently and irresponsibly.

Instead of bequeathing vast wealth to his family, Carnegie ensured their comfort while leaving them with limited funds. He firmly stated, “the parent who leaves his son enormous wealth generally deadens the talents and energies of the son.” Almost all of his fortune was devoted to philanthropic endeavors. By the time of his passing, he had already donated over $350 million. When faced with the challenge of disbursing his wealth swiftly, he established the Carnegie Corporation, which would carry out his philanthropic vision long after he was gone, supporting deserving causes.

To this day, the Carnegie Corporation persists in its philanthropic work, upholding Andrew Carnegie’s ideals. During his final years, he dedicated himself to the pursuit of world peace. Astonishingly, he even attempted to “bribe the Germans to stop WW1” and advocated for collaboration among world leaders to avoid any form of conflict. The Carnegie Corporation’s ongoing philanthropic efforts serve as a testament to his enduring commitment to making the world a better place.

Interpretations and Perspectives on Andrew Carnegie’s Philanthropy

When contemplating Andrew Carnegie’s legacy, many individuals approach his philanthropy with differing perspectives. Some choose to view his charitable acts through a cynical lens, arguing that his philanthropy stemmed from a guilty conscience. They point to his involvement in events such as the Johnstown flood, the Homestead tragedy, poor working conditions, mistreatment of workers, and numerous accidents and fatalities in his factories. It is plausible that he saw philanthropy as a means of atonement, an effort to rectify past wrongs.

Alternatively, others believe that his philanthropy was driven by self-preservation, ensuring his name would be remembered positively through the foundations, charities, and buildings he established. In essence, he prioritized leaving behind a lasting and favorable legacy. Some even suggest that his rivalry with Rockefeller played a role, as both billionaires seemingly competed to outdo each other in philanthropic endeavors, striving to be recognized as the greater benefactor.

While all these factors may have influenced Carnegie’s actions, it is evident that he harbored a genuine desire to assist others. His repeated statement, “the man who dies rich dies disgraced,” emphasizes his belief that the wealthy have an obligation to use their fortunes to improve society as a whole. In his influential article, “The Gospel of Wealth,” Carnegie advocated for corporate philanthropy, setting a precedent that inspired future billionaires to consider giving back to society. It is only fair to acknowledge that Andrew Carnegie’s contributions have had a profound impact on humanity. Through his steel industry advancements and unparalleled philanthropic endeavors, he improved the supply and efficiency of steel while positively influencing countless lives through his substantial donations, particularly in the field of education.

In summary, Andrew Carnegie’s legacy is one of philanthropy and social progress. His impact on society resonates through institutions such as Carnegie Hall, the Carnegie Corporation, and the ongoing philanthropic work carried out in his name. While some may question his motivations, there is no denying the tremendous good he accomplished during his lifetime. From revolutionizing the steel industry to his unparalleled generosity, Andrew Carnegie’s contributions have left an indelible mark on the world, ensuring that his legacy as a philanthropist lives on for generations to come.