Mongolia, with its immense size and captivating features, stands as one of the most intriguing countries in the modern world. Its land area surpasses that of Texas, making it more than twice its size. If we were to superimpose Mongolia onto the United States, it would stretch across the historical South, extending from Philadelphia in the East to Dallas in the West. However, this captivating landlocked nation is nestled within the Eurasian continent, surrounded by vast stretches of land, which separates it from the ocean. Consequently, Mongolia holds the distinction of being the largest landlocked country worldwide without access to an internal sea.

While Kazakhstan is technically larger than Mongolia, it boasts a coastline of nearly 1900 kilometers along the internal Caspian Sea. This grants Kazakhstan the ability to engage in maritime trade with neighboring countries such as Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. In contrast, Mongolia lacks direct access to large bodies of water, further emphasizing its unique geographical characteristics.

Mongolia’s Vast Landscapes and Sparse Population

Mongolia, due to a combination of factors including its geographical attributes, stands as one of the most sparsely populated countries on Earth. Covering more than one and a half million square kilometers, Mongolia ranks as the 18th largest country globally in terms of land area. Surprisingly, this vast expanse is home to a relatively small population of approximately 3.3 million people. To put this into perspective, it is comparable to the population residing in and around San Diego, California.

Consequently, Mongolia boasts an astonishingly low average population density of around 2.1 people per square kilometer, the lowest among all sovereign countries. To provide context, this density is approximately one-third lower than the second and third least densely populated countries in the world: Australia and Namibia. Notably, both Australia and Namibia have significant portions of their territories covered by vast, uninhabitable deserts. Nonetheless, Mongolia manages to surpass even these countries in terms of emptiness.

At first glance, Mongolia may seem similar to Australia due to the presence of multiple large population centers scattered across the country. Australia, with five cities boasting over one million residents each, exhibits a more evenly distributed population compared to Mongolia. Contrary to the misconception of Mongolia being a massive city-state with an abundance of surrounding empty land, this captivating country is much more diverse.

Ulaanbaatar: The Centralized Heart of Mongolia

The capital city of Ulaanbaatar, with its population of approximately 1.6 million, serves as both the largest city in Mongolia and its administrative core. In terms of size, Ulaanbaatar can be compared to Barcelona, Spain, as both cities boast a similar number of inhabitants. Astonishingly, Ulaanbaatar alone accommodates around 48% of Mongolia’s total population.

As a result, Mongolia holds the distinction of being one of the most highly centralized countries globally. Given that Ulaanbaatar occupies a mere 0.3% of Mongolia’s land area, a peculiar scenario unfolds. Approximately 48% of the population, equivalent to 1.6 million individuals, resides on this tiny fraction of land, while the remaining 52% of the population (around 1.7 million people) is dispersed across the remaining 99.7% of the country.

The concentration of the population in Ulaanbaatar significantly skews the average population density across Mongolia as a whole. By excluding the city’s land area from the calculation, the remaining 99.7% of Mongolia features an average population density of merely 1.1 people per square kilometer. This figure highlights the striking emptiness of the country and positions it as three times less populated than Australia and Namibia on average.

Further contextualizing this statistic, 99.7% of Mongolia’s land holds a population density that is almost half as sparse as Lapland, the far northern region of Finland. Stretching beyond the Arctic Circle, Lapland represents the least densely populated part of the European Union. It is within this vast, empty expanse of Mongolia that roughly one-third of its population continues to lead a nomadic herding lifestyle, reminiscent of the era of Genghis Khan over 800 years ago.

Unraveling the Mystery: The Geography and Climate of Mongolia

To understand the unique population distribution and the persistence of Mongolia’s sparseness into the 21st century, it is crucial to delve into the country’s geography and climate. Mongolia’s territory spans across the high Mongolian Plateau, a region of elevated terrain in Central Asia. Surrounded by towering mountain ranges on all sides, Mongolia finds itself contained within this expansive plateau.

3.1 The Mongolian Plateau and its Elevation

The Mongolian Plateau spans an impressive range of altitudes, stretching from 1000 to 1500 meters above sea level. Situated approximately 800 kilometers away from the nearest oceanic body, the Yellow Sea, Mongolia’s borders within the high Plateau isolate it from the direct influence of oceanic moisture.

Due to the elevated position and significant distance from the Indo-Pacific region, the Mongolian Plateau rarely experiences the arrival of moist monsoon winds that carry rainfall from the Pacific. This scarcity of moisture is further compounded by the plateau’s proximity to Siberia, which exerts a profound influence on Mongolia’s climate and its capacity to support human habitation.

3.2 The Advent of Winter

As summer draws to a close around August, the days in Northern Asia gradually shorten, heralding the approach of winter. The cold and dry air originating from Siberia, propelled by the frigid Arctic Ocean winds, intensifies as it flows into the region. Unlike the Arctic air, which forms over sea ice and radiates heat efficiently, the Tundra environment of Siberia leads to even colder temperatures.

Between September and April, the harsh Siberian air, characterized by extreme cold and low moisture content, traverses Northern Eurasia, reaching the Mongolian Plateau in particular. Consequently, winters in Mongolia are consistently bitterly cold and dry. The cold air settles within the lower elevated river valleys and basins of the plateau, enveloping the northern parts of the country in severe cold temperatures. However, as one moves further south, the severity of the cold gradually diminishes.

3.3 Winter Realities in Mongolia

While the median temperature across the country in January stands at -30 degrees Celsius, it’s essential to recognize the occurrence of sudden and intense cold snaps and blizzards throughout Mongolia during the extended winter season. Within a mere 24 hours, temperatures can fluctuate by as much as 30 degrees Celsius. Regional lows of -40 degrees Celsius are commonplace in the north of the country during this time.

The freezing temperatures dominate Mongolia’s rivers and lakes, rendering them impassable during the winter months. Many smaller rivers freeze entirely, right down to their beds, making them impractical for transportation or irrigation for the majority of the year.

Ulaanbaatar, the capital and largest city of Mongolia, experiences frost-free conditions for only approximately three and a half months each year, spanning from mid-May to the end of August. With an average annual temperature of -2.9 degrees Celsius (27 degrees Fahrenheit), Ulaanbaatar holds the distinction of being the coldest capital city on Earth. However, during the short Mongol summers, temperatures can soar to staggering heights of up to 38 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit) in the southernmost regions, and even reach 33 degrees Celsius (91 degrees Fahrenheit) in the capital.

3.4 The Scarcity of Rainfall

Mongolia’s location on the highly elevated Mongolian Plateau prevents it from receiving substantial rainfall. The southern region faces obstructions from the towering Himalayas and Kunlun Shan mountains, hindering rain-bearing winds from that direction. Similarly, the western Altai Mountains, along with the Mongol-Tai and Gobi-Altai sub-ranges, act as formidable barriers to rain infiltration. Moisture-rich winds approaching from the south deposit their moisture as snowfall on the mountainsides facing away from Mongolia, leaving the winds mostly dry by the time they traverse the Mongolian Plateau.

3.5 Dry and Sunny Weather

Between September and April, the arrival of dry, cold high-pressure air from Siberia dominates the Mongolian Plateau. This displaces any low-pressure moist air that could potentially bring rainfall. Consequently, the winter season in Mongolia remains marked by clear skies and an absence of clouds. This unique meteorological phenomenon makes Mongolia one of the sunniest countries globally, enjoying approximately 257 cloud-free and sunny days each year. Paradoxically, this means that Mongolia experiences minimal precipitation during this extended winter period. Instead, any form of moisture primarily manifests as snow or frost, carried by the winds blowing from Siberia.

3.6 Limited and Unpredictable Summer Rains

During the summer months (May to August), the weakening and retreat of the high-pressure cold and dry system from Siberia allow some rainy air to penetrate the Mongolian Plateau from the north. Northern Mongolia experiences relatively higher rainfall levels compared to the southern regions. However, it is crucial to note that the bulk of northern Mongolia’s rainfall occurs between June and August when the Siberian high-pressure system is at its weakest. Beyond the summer season, rainfall becomes sporadic and unreliable, making it challenging to rely on for agricultural purposes.

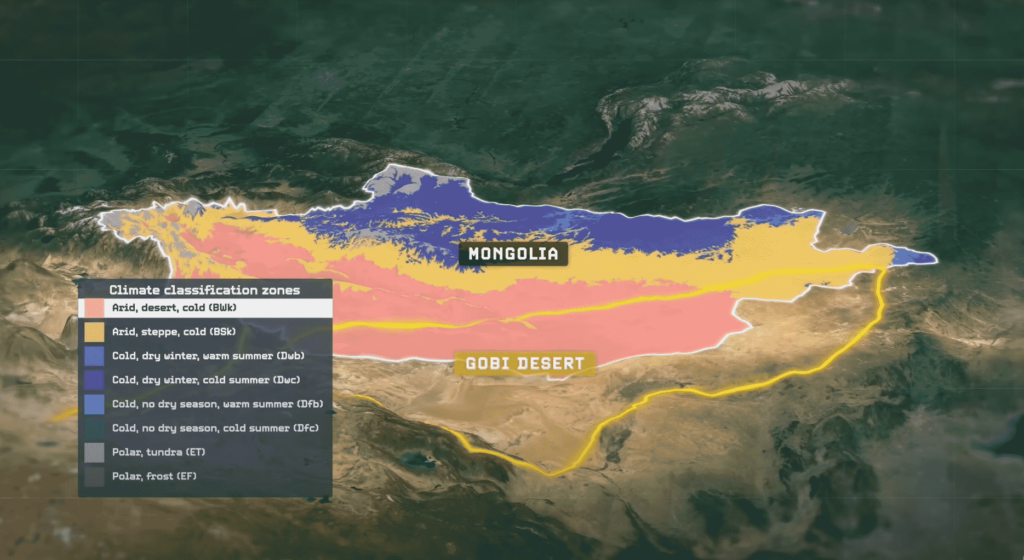

3.7 The Gobi Desert

The unique climate in Mongolia, characterized by meager rainfall and extreme cold, has given rise to the expansive Gobi Desert in the southeastern part of the Mongolian Plateau. As the sixth-largest desert globally, the Gobi Desert is both extremely cold and arid, experiencing long periods without any precipitation. These climatic conditions are reflective of Mongolia’s overall climate, which is dominated by cold, dry, and windy conditions. The southernmost third of the country comprises a cold, arid desert, while the rest primarily consists of cold, arid steppe covered in seemingly endless grasslands. Limited forest coverage is observed in the northern regions.

3.8 Arable Land and Agricultural Challenges

Given the climatic limitations, only a mere 0.4 percent of Mongolia’s vast land is considered suitable for crop cultivation and agriculture. Comparatively, only Djibouti, Iceland, and Oman have a lower percentage of arable land, excluding small Pacific island states and city-states. Despite being the 18th largest country globally in terms of overall land area, Mongolia possesses less arable land than Albania, a country over 54 times smaller. Consequently, establishing large-scale settled agricultural societies across the Mongolian Plateau is virtually impossible.

Nomadic Herding: A Way of Life Shaped by Geography and Climate

The vast and expansive steppes of Mongolia offer an ideal environment for herding and ranging livestock, thanks to their open grasslands. Compared to settled farms and cities, these nomadic herders can easily traverse the steppes, adapting to different areas based on the seasons. During winter, herders gather their livestock in valleys, utilizing the shelter provided by surrounding mountains to shield them from Siberian cold winds. Conversely, in the summer, they relocate to the wide, grass-covered steppes, ensuring ample grazing for their herds. This long-standing lifestyle, predominantly followed by the people of the Mongolian Plateau for thousands of years, utilizes approximately 65 percent of Mongolia’s land for pastoral purposes. Even today, a third of the population continues to embrace the traditional nomadic herding lifestyle passed down through generations, a way of life enforced by the region’s unchanging geography and climate.

4.1 Challenges of Herding and Pastoralism in Mongolia

However, herding and pastoralism in Mongolia come with their own set of challenges. Winters in Mongolia are bitterly cold, accompanied by clear skies devoid of clouds. Harsh blizzards and freezing rainstorms can still occur, wreaking havoc on herders and their flocks. In severe cases, blizzards from Siberia can devastate entire livestock populations, either causing the animals to freeze to death or covering their vital grazing grass with a thick layer of frost. The winter of 2009-2010 serves as a grim reminder of these perils, as freak blizzards in Mongolia resulted in the loss of over 8 million livestock. Many nomadic herders faced complete devastation, leading them to abandon their traditional lifestyle and seek refuge in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia’s sole major urban center. The harsh winter storms and accompanying droughts on the Mongolian Plateau have been instrumental in shaping the nomadic lifestyle for thousands of years. When grasslands are decimated and livestock perish due to extreme weather events, desperate nomads, left with nothing, are compelled to travel in search of greener pastures.

The Eurasian Steppe: A Vast and Dynamic Region

The Mongolian Plateau’s steppes are part of the greater Eurasian steppe, a near-continuous expanse that stretches from Anatolia in the east to Hungary in the west. This immense steppe has witnessed the rise and fall of nomadic horse societies for millennia, allowing them to traverse its predominantly flat terrain like a pre-industrial superhighway. Climate-induced catastrophes in one region of the steppe often forced nomads to migrate to new territories, either within or beyond the steppe itself. Throughout human history, this vast steppe became the origin of numerous pneumatic migrations and invasions, with nomadic forces venturing into sedentary agricultural societies that emerged around the steppe, including Russia, Europe, the Middle East, and China. These regions experienced the impact of nomadic invasions from ancient times, such as the Xiongnu, Scythians, and Huns, to later groups like the Turks, Mongols, and Manchu.

In modern times, Mongolia faces additional challenges, exacerbating the pre-existing climate-related issues and their impact on livestock rearing and sustenance. Throughout the 20th century, Mongolia was under the rule of an authoritarian Communist regime, which enforced strict regulations on the size of livestock herds allowed in the country. This controlled approach maintained an ecological balance.

The Growing Impact of Cashmere Production in Mongolia

In the 1990s, the global cashmere industry emerged as a lucrative multi-billion dollar business. Exploiting the newfound freedom from Communist regulations, many Mongolian herders sought to capitalize on this trend. Consequently, they transitioned from traditional sheep herds to goat herds, which produce valuable cashmere wool. Over time, Mongolia has emerged as the second-largest global producer of cashmere fibers, supplying approximately 40 percent of the world’s cashmere.

However, the rapid growth of the cashmere industry has come at a significant ecological cost. Goats, unlike sheep, pose a greater threat to Mongolia’s steppe environment. Their grazing habits result in severe damage to the grasslands. Goats tend to nibble at the grass roots while feeding, preventing regrowth. Moreover, their sharp hooves cause additional harm to the upper layers of soil, which are then carried away by the prevailing winds of the steppe.

These destructive actions have led to a rise in dust storms, air pollution, and droughts across the country, intensifying the challenges faced by herders. In combination with the impacts of global climate change, Mongolia is experiencing the northward expansion of the inhospitable Gobi Desert. This expansion occurs at a rate of approximately six to seven kilometers per year, further diminishing the available land for nomadic herders.

Increasing Frequency of Extreme Weather Events

Mongolia is also witnessing a rise in the frequency of extreme weather events. Prior to the year 2000, the country typically experienced around 20 such events, including droughts, blizzards, and extreme temperatures, each year. However, since 2000, this number has nearly doubled, with an average of approximately 40 extreme weather events occurring annually.

As a result of these factors, an increasing number of nomadic herders are being displaced from the countryside. In the past, such circumstances would have triggered mass migrations resembling the unstoppable horse invasions seen under Genghis Khan. However, in the modern era, herders are being compelled to concentrate in the city of Ulaanbaatar, which occupies only 0.3 percent of Mongolia’s land but is home to 99.7 percent of its population. The outskirts of the city now showcase suburbs constructed from traditional nomadic Mongolian gers, highlighting the impact of this phenomenon.

Climate Change and Development Challenges

Climate change not only amplifies the frequency of extreme weather events and the expansion of the Gobi Desert but also hinders Mongolia’s development in various other ways. Among these challenges is the issue posed by the country’s extensive permafrost layers located beneath the surface. Throughout modern-day Mongolia, the majority of the land is covered by permafrost, where the subsoil freezes during the harsh winters and thaws during the hot summers.

Building in such an environment presents formidable obstacles. Thawing permafrost beneath construction projects causes the soil to settle and become unstable, leading to sinking and deformation of structures. Foundations sink, apartment walls crumble, paved roads and runways develop cracks, and pipelines rupture. Disturbingly, Mongolia has experienced a temperature increase exceeding the global average since 1940. The average annual temperature in the country has risen by at least 1.8 degrees Celsius, exacerbating the aridity and accelerating permafrost thawing.

Consequently, Mongolia’s highways, railroads, pipelines, airports, apartment buildings, and other infrastructure are at risk unless subjected to constant and costly maintenance.

As permafrost continues to thaw, the limitations on Mongolia’s development and its capacity to accommodate a large urban population outside the capital will only intensify. Additionally, numerous historical factors have compounded the negative impact on Mongolia’s present-day population, exacerbating the challenges faced by the country.

The Rise and Fall of the Mongol Empire

In the early 13th century, Genghis Khan emerged as a unifying force, bringing together the Mongol tribes. With their mighty horses, the Mongols embarked on a conquest that echoed across the vast Eurasian steppe. This formidable empire, unparalleled in size, stretched from China and Korea in the east to Iran in the south, encompassing a significant portion of Russia, Ukraine, and Poland in the west. However, as time passed, the empire began to fracture due to internal conflicts among the Mongol factions.

9.1 The Dissolution of the Mongol Empire

After ruling China for almost a century, the Mongol Yuan Dynasty faced its downfall in 1368 at the hands of the Han-lee Ming Dynasty. Subsequently, the Mongols retreated to the Mongolian plateau, establishing a diminished state called the Northern Yuan. This new territory encompassed present-day Mongolia, Inner Mongolia (now part of China), and parts of Southern Siberia in modern-day Russia.

By the early 17th century, the once-mighty Mongol Golden Horde in Russia and the Ilkhanate in Iran had disintegrated. Meanwhile, the Manchu tribes of Manchuria sought to consolidate their control over Inner Mongolia, gradually weakening the Northern Yuan. Eventually, in 1644, the Northern Yuan fragmented into several independent entities. Simultaneously, the Russian Empire expanded its dominion across Siberia, and the Manchu launched an extensive invasion of the Ming Dynasty, resulting in the establishment of the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty.

9.2 Conquest and Its Consequences

Under the Qing Dynasty, a series of invasions and conquests took place. The Qing targeted Outer Mongolia in 1687, Tibet in 1723, and modern-day Xinjiang in 1755. However, this expansion brought unintended consequences, reminiscent of the encounters between Europeans and Native Americans in the New World. The Mongols, like the Native Americans, had led a nomadic lifestyle, never residing in densely populated urban centers alongside their livestock. Thus, they lacked immunity to the diseases that plagued settled Eurasian societies for centuries.

As the Han Chinese soldiers advanced deeper into the Mongolian plateau in the late 17th century, they inadvertently introduced smallpox, much like the Europeans did in the New World. The devastating impact of smallpox, combined with military violence and deliberate genocide ordered by the Qing Emperor, resulted in the decimation of the Dzungar Mongol population. It is estimated that between half a million and 800 thousand people, accounting for 50 to 80 percent of the Dzungar Mongols, perished.

Furthermore, the Russian Empire’s relentless expansion in Siberia instilled fear in the Qing Dynasty, which sought to reinforce its hold over Inner and Outer Mongolia. To achieve this, the Qing government encouraged large-scale Han Chinese resettlements in the Mongolian plateau. This influx of settlers brought with them subtle diseases, including smallpox, and fostered the dissemination of a new religion in the region.

Buddhism in Mongolia

Over centuries, Tibetan Buddhism underwent a profound transformation on the Mongolian plateau. It gradually supplanted the secular authority of the previous rulers, establishing itself as the dominant power. As a result, the Tibetan Buddhist Church gained control over approximately 20 percent of Mongolia’s wealth. In the harsh expanse of the Mongolian steppes, where land held little value, livestock, horses, and human lives were deemed invaluable.

During the early 20th century, a considerable number of Mongolia’s nomadic herders devoted their sons and families to various Buddhist monasteries. This act was driven by both personal religious conviction and the desire to gain favor from the dominant legal and economic powers of the steppe. Consequently, Mongolia boasted hundreds of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, and approximately one in three men in the country became dedicated Buddhist monks, forsaking marriage and children. This situation presented a significant constraint on population growth, as a considerable portion of the male population withdrew from the dating and reproductive pool.

10.1 The Revolution and the Theocratic State

In late 1911, a revolution within the Qing Dynasty led to the collapse of the Empire and the subsequent establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). Taking advantage of the ensuing chaos, the Tibetan Buddhist clergy in Mongolia declared the independence of Outer Mongolia, renaming it simply Mongolia. Thus, Mongolia entered a phase of theocratic rule, with Buddhism as its guiding principle. However, the ROC initially refused to acknowledge Outer Mongolia’s independence, asserting itself as the Qing Dynasty’s rightful successor. Nonetheless, the intervention of the Soviet Union to maintain Mongolia’s independence coerced the ROC into eventually recognizing it. Mongolia became a communist satellite state under Soviet influence during the 1920s, eluding the Republic of China’s attempts to reclaim it.

10.2 Suppression of Buddhism and Population Shifts

The advent of the People’s Republic of Mongolia, an atheist and communist regime, marked a significant turning point. The new government sought to dismantle the feudal Buddhist theocracy that had governed the country prior to its establishment. By the 1940s, the Communists had either killed or converted almost every Buddhist monk in Mongolia, effectively eradicating Buddhism as a dominant religious force. Only one monastery, located in the capital, was permitted to operate with a meager hundred monks throughout the Communist era, lasting until 1990.

Demographic Transformations

The 1970s witnessed a surge in Mongolia’s birth rate, peaking when the average Mongolian woman gave birth to 7.3 children. However, with the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1990 and the subsequent collapse of the Mongolian Communist regime, the country underwent an economic and demographic shock akin to other post-Soviet states. Consequently, the birth rate experienced a steep decline, reaching an average of 2.1 children per woman by 2000. This sharp decrease represented a significant departure from the previous three decades, indicating a major demographic shift.

Mongolia’s sparsely populated vast landscapes have made it susceptible to external influences, particularly from its larger neighbors, Russia and China. Throughout history, these two countries have alternated in their control over Mongolia, starting with the Qing Empire’s conquest of Outer Mongolia in the late 17th century. True independence has been short-lived for Mongolia, with brief periods of self-governance amidst a larger geopolitical context.

Mongolia’s Path to Independence and Geopolitical Challenges

The Qing dynasty exerted direct control over what they referred to as Outer Mongolia for over two centuries. However, it was only in the early 20th century that Mongolia truly gained independence, lasting from 1911 until 1924. Unfortunately, its independence was short-lived as it became a satellite state of the Soviet Union until 1990. Within the last three centuries, Mongolia has experienced its longest period of genuine autonomy, lasting just over 30 years. If it had not fallen under Soviet influence in the 1920s, the People’s Republic of China might have invaded and assimilated Mongolia, similar to their actions in Tibet between 1950 and 1951.

12.1 Recognition of Mongolia’s Independence

The People’s Republic of China acknowledged Outer Mongolia’s independence and recognized it as Mongolia in 1949, when their victory in the Chinese Civil War seemed inevitable. This move primarily aimed to appease the Soviets, who desired to maintain Mongolia as their satellite state. On the contrary, the Republic of China, which relocated to Taiwan, did not recognize Outer Mongolia’s independence until as late as 2002.

12.2 Inner Mongolia’s Struggle for Independence

In contrast to Outer Mongolia, Inner Mongolia was unable to achieve the same level of independence. It has remained an integral part of various Chinese states since the Manchu and the Qing established control over it in the early 1600s. Today, Inner Mongolia is an autonomous region of the People’s Republic of China and is home to a larger Mongol population than the independent state of Mongolia itself. Inner Mongolia boasts approximately 5 million ethnic Mongols, while the Mongolian state has around 3.3 million.

Despite the significant Mongol population in Inner Mongolia, ethnic Mongols are a minority in their own region. Centuries of Han Chinese colonialism and migration to the Mongolian Plateau from other parts of China have resulted in Han Chinese constituting approximately 79 percent of Inner Mongolia’s population. In comparison, the Mongols themselves account for only 17 percent.

Mongolia’s Geopolitical Challenges

The present-day independent state of Mongolia remains a relatively small nation, home to merely 3.3 million people. It finds itself sandwiched between two giants: Russia, with a population of 146 million, and China, with over 1.4 billion. This situation has often been likened to sharing a den with a bear and a dragon. To exacerbate matters, Mongolia heavily relies on both Russia and China for its survival. Russia supplies 98 percent of Mongolia’s oil and gasoline resources through imports, while 90 percent of Mongolia’s exports, in terms of value, are directed towards China.

Furthermore, Mongolia depends greatly on China for the processing of its primary resources, such as raw cashmere wool, coal, copper, iron, and gold. These resources are transported to Chinese factories for further refinement. Consequently, Mongolia is heavily reliant on Russia for its energy requirements and heavily dependent on China as its primary export market. As cooperation between China and Russia strengthens, Mongolia finds itself increasingly enclosed within geopolitical constraints.

Mongolia in the Face of Shifting Geopolitical Dynamics

Following Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, the Mongolian government has displayed hesitance in expressing any form of condemnation or concern. While Europe has started reducing its imports of Russian oil and gas, Russia has shifted its focus towards the Chinese market. This involves the construction of a new natural gas pipeline, known as the Power of Siberia 2, which is set to commence in 2024. This pipeline will directly link China’s energy-hungry economy with Russia’s extensive natural gas fields in the Yamal Peninsula, previously catering to the European Union.

The most direct route for this pipeline will pass through the Yamal Peninsula, traverse Siberia, and cut across Mongolia, reaching China’s urban centers in the North China Plain. Mongolia had no choice but to accept the pipeline’s passage through its sparsely populated territory, spanning hundreds of kilometers. Ultimately, this pipeline will help Russia generate more revenue amid stringent Western financial sanctions, while offering China a direct land route to fulfill its energy needs.

China’s foreign policy objective of gaining control over Taiwan has been a significant concern for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). One primary obstacle they face is the potential intervention of the United States Navy, which could enforce a blockade on the Malacca Strait. This narrow strait serves as a crucial route for China’s petroleum and liquefied natural gas imports from the oil and gas-rich states of the Persian Gulf. A successful blockade would severely cripple the Chinese economy and hamper their ability to engage in military activities. However, by reducing dependence on maritime energy imports and establishing land-based alternatives such as pipelines from Russia through Mongolia, China can enhance its resilience to a hypothetical American naval blockade and strengthen its military capabilities during an attack on Taiwan.

China’s Reducing Dependence on Maritime Energy Imports

To mitigate the risk posed by a potential naval blockade in the Malacca Strait, China must seek alternative energy sources that are less vulnerable to disruption. Currently, the People’s Republic heavily relies on imports via the strait for approximately 70% of its petroleum and liquefied natural gas supply. By diversifying their energy imports, China can decrease its dependence on maritime routes.

China is actively pursuing the construction of pipelines directly from Russia to China through Mongolia. This strategic move enables China to reduce its reliance on maritime energy transportation. By increasing land-based energy imports, China aims to ensure a steady supply of resources even if the Malacca Strait becomes inaccessible due to a blockade. These pipelines offer a more secure and reliable alternative.

A reduced dependence on maritime energy imports not only safeguards China’s economy but also enhances the operational capabilities of its armed forces. By securing alternative energy sources, China’s People’s Liberation Army and Navy can focus on their primary objective—engaging in military actions—without being overly concerned about the vulnerability of their energy supply lines. This, in turn, provides a strategic advantage during a potential attack on Taiwan.

Also Read: Is Fusion Energy Really the Future or Just Hype?

Mongolia’s Delicate Foreign Policy Position

Mongolia, nestled between two formidable powers—Russia and China—faces a complex geopolitical landscape. Historically, the nation has had to navigate the competing interests of these neighboring giants while preserving its own sovereignty. In recent times, as Russia’s authoritarian tendencies grow more pronounced and China’s assertiveness strengthens, Mongolia finds itself at a crossroads, struggling to maintain its independent foreign policy.

16.1 The Russian Factor

Russia’s increasingly authoritarian regime has manifested itself through overt military aggression in Europe. Invading Georgia and Ukraine, and propping up separatist movements in Moldova, Russia’s actions paint a worrisome picture for Mongolia. Aware of Russia’s expansionist tendencies, Mongolia must carefully weigh the consequences of engaging in cooperation that could potentially compromise its sovereignty.

16.2 China’s Quest for Supremacy

On the other hand, China’s aspirations as a global superpower raise concerns for Mongolia’s independent foreign policy. The People’s Republic of China envisions itself as the successor to the Qing Empire, under whose direct rule Mongolia fell for centuries. While Tibet and Xinjiang were quickly incorporated into the Chinese state, Mongolia’s historical ties and geographic proximity warrant apprehension. Mongolia’s cautious approach is understandable, given the potential ramifications of disregarding China’s regional ambitions.

The Dilemma: Cooperation or Consequences

Mongolia finds itself caught between a rock and a hard place—balancing its interests between the bear and the dragon. With a population of 3.3 million and vast tracts of uninhabited land, Mongolia’s vulnerability is evident. Refusing cooperation with China and Russia risks inviting aggression, as history has shown. To safeguard its sovereignty, Mongolia must tread a fine line, seeking diplomatic channels that preserve its independence without jeopardizing its fragile position.

In the face of these challenges, Mongolia must adopt a pragmatic approach to safeguard its independent foreign policy. By engaging in strategic cooperation while setting clear boundaries, Mongolia can navigate the delicate geopolitical landscape. Strengthening ties with countries that share its commitment to democratic values and respecting its sovereignty would enhance Mongolia’s bargaining power and offer a counterbalance to the influence exerted by its formidable neighbors.

Preserving Mongolia’s Identity

Above all, Mongolia must remain steadfast in preserving its cultural identity and national heritage. By promoting its rich history, unique traditions, and diverse landscapes, Mongolia can establish itself as a vibrant and appealing destination for international cooperation, trade, and tourism. Embracing its distinctive qualities will strengthen Mongolia’s position on the global stage, fostering relationships that go beyond geopolitical concerns.